Alternative Aviation Fuels (SAFs)

Aircraft currently use fossil-based kerosene as fuel.

One solution to aviation’s decarbonisation problem is the development of alternative fuels, which are based on non-fossil based feedstocks. Some examples include using used cooking oil, black bin bag waste, ethanol or waste forestry or crop residues. Some countries permit the use of biofuels (based on feedstocks such as palm oil), but these are not permitted in the UK due to the real concerns about deforestation and competition for scarce farmland for growing fuels, not food crops.

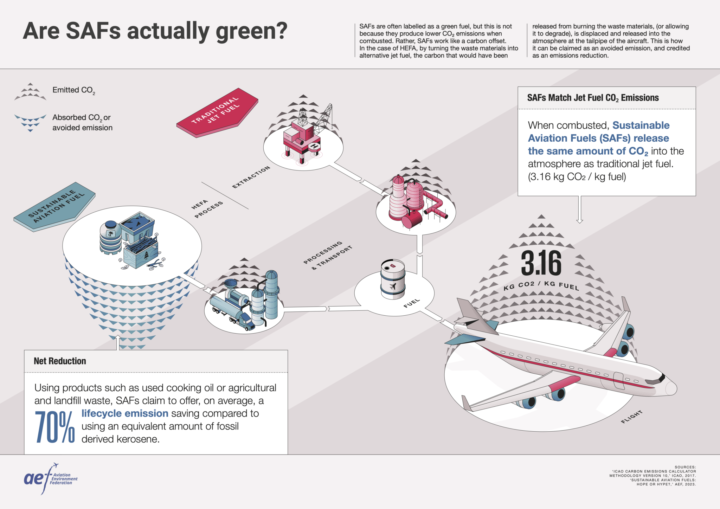

These fuels have been dubbed “sustainable” because in theory they represent a closed loop of carbon dioxide emissions – they continue to emit CO₂ when they are combusted, but this is absorbed by plant growth or reduced because the CO₂ from the decomposition of waste is turned into fuel. Government estimates suggest that SAFs can reduce emissions on a lifecycle basis of up to 70%; AEF is clear that these emissions savings must be constantly assessed and monitored, and not merely assumed based on underlying methodologies.

SAFs still emit the same amount of CO₂ when they are burned as traditional jet fuel

The UK SAF mandate

In 2025, the UK government introduced a SAF mandate which is an obligation on fuel suppliers to supply a minimum of 2% SAF alongside traditional kerosene – this proportion increases to 10% by 2030 and 22% by 2040. The SAF mandate also includes a small percentage of e-fuels, or synthetic fuels, which should be developed by 2030. E-fuels use extracted CO₂ as a feedstock, which means they are capable of actually reducing emissions from the atmosphere (rather than just recycling them with less advanced SAFs), however they are very energy intensive and expensive to produce.

Alongside the SAF mandate, the UK government also introduced a Revenue Certainty Mechanism (RCM), which is a guarantee to producers that they will receive a strike price for fuel they produce – this is to be funded through a levy on the fuel supply industry and not taxpayer’s money. There is also a mandate in the EU known as Refuel EU, and in the US there are subsidies for SAF producers. However, as things stand, the global supply of SAF is still not sufficient to meet any of the mandates, and the fuel continues to cost at least twice as much as kerosene.