28th October, 2022

Greenwashing in the aviation industry

What is Greenwashing? Greenwashing is the practice by a company of leading consumers to believe that it is improving its environmental performance while making no significant change.

In a recent study carried out by Booking.com, 83% of global travellers regarded travel sustainability as vital. As travellers get more eco-conscious, it’s clear why aviation corporations seem to spend a lot of time and money trying to appeal to them.

But this is hard to do when the technology that will decarbonise your industry is still in its infancy. We have yet to see a single zero-emission flight on a commercial-sized plane. This limits airlines’ options for what they can market to environmentally-conscious consumers.

DeSmog, a charity that look into climate misinformation, found that only 10% of airline ads reference sustainability. The majority choose to ignore the issue and focus on cheap or promoted flights. When airline adverts did address emissions they mention offsetting, sustainable aviation fuels, fuel efficiency and future climate goals.

None of these options can guarantee a carbon-neutral flight. So, airlines rely on inference, consumer ignorance and misinformation to make it seem as though their flights are less polluting. This is greenwashing.

In this article, we investigate three sustainability claims that often fly under the radar.

1. Air miles are never green

In March 2022, Etihad Airways began offering air miles to football fans who recycled plastic bottles. The response from green campaigners was one of outrage. Many took issue with the claim that putting bottles in the bin and scanning a nearby QR code to get rewards would ‘help make a difference to the planet’.

Trading more recycling for more flying won’t help the climate crisis. It gives fans a false sense that they are being green while portraying Etihad Airways as climate-friendly. We need to reduce waste, increase recycling and reduce CO2 from flying.

There is even an issue with equivalence. One air mile on an economy, long-haul flight, emits about 117g of CO2. Recycling a bottle saves 34g of CO2 in the production of a new one, less than a third of the CO2 associated with an air mile. After we use a multiplier for the non-CO2 impacts of flying, the difference becomes even greater. The impact of taking a plane rises to over 200g of CO2 per mile.

This suggests that someone would need to recycle at least six bottles to get one ‘Etihad Guest Mile’. And further questions arise. Etihad doesn’t say HOW they plan to recycle these plastic bottles. We are only told that Manchester City Stadium and Etihad are going to ‘turn the plastic bottles into something special in the future,’ and to ‘watch this space’. Will they be recycled? Turned into fuel? To date, neither Etihad nor Manchester City Stadium has announced what ‘special’ project this stunt was driving towards.

Like Etihad Airways, Qantas also rewards people for making ‘green’ choices by offering incentives to fly more. Despite having a target to reduce its emissions by 25% by 2030, Qantas introduced a ‘Green Tier’ to reward frequent flyers. They receive air miles when they make ‘sustainable’ choices like offsetting, testing their sustainability knowledge and buying eco wine.

In both of these examples, there is a false equivalence. Etihad’s campaign leads people to believe that plastic bottles are equivalent to air miles. Qantas lead consumers to believe that in exchange for showing off their sustainability knowledge, they can fly more.

Instead, we should keep this principle in mind: air miles can never be green. Any ‘green’ scheme or reward system which encourages people to fly more cannot claim to be sustainable while flying remains such a polluting activity.

2. Voluntary offset schemes and lack of transparency

What are carbon offsets? Carbon offsets work on the assumption that consumers can compensate for the CO2 associated with their flight by funding carbon reduction projects elsewhere. For example, by planting trees. Even contributing to the purchase of sustainable aviation fuel – which emit just as much carbon as kerosene when burnt but have lower lifecycle emissions – are thought of as a type of offset.

Earlier this year, Wizz Air was named the most sustainable airline in Europe. This was due to its young, relatively efficient fleet, which has recently grown by 30 planes. They also launched virtue signalling measures such as going paperless, banning single-use plastics and offering a carbon offset programme. Carbon offsetting schemes are common throughout the industry, but some fail to meet basic regulatory standards. There have long been calls to make offsetting schemes more transparent.

One problem is that the positive impacts of many – if not all – offsets are hard to scrutinise. Voluntary offset schemes remain largely unregulated and greenwashing can be rampant.

Some schemes can be easy to see through. For example, Ryanair was forced to drop two schemes, a reforestation project in Ireland, and a whale and dolphin counting scheme. Both were found to be ineffective at reducing emissions.

While ditching controversial schemes limits the greenwashing effect, it does not eradicate it. This is a systemic problem. A paper published in 2021, found that 44% of the claims about voluntary offsets made by the 37 airlines studied were misleading.

Offset companies provide an excuse for polluting industries to keep polluting. All sectors will need to achieve net zero emissions in the coming decades to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement and limit global warming. Many offset schemes help to pay for measures that should be happening anyway.

Perhaps the message is starting to get through. Easyjet announced in September 2022 that it would stop its voluntary purchase of offsets at the end of the year to focus on sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs), carbon capture and increased plane efficiencies.

3. Carbon-neutral airports do not equal carbon-neutral flying

Many airports say they are carbon neutral or aim to become net zero with various dates ranging from 2030 to 2050. But there’s a catch. Most of these claims only apply to emissions on the ground. This includes heating and airport vehicles and staff, passenger and freight journeys to and from the airport. Once you include the CO2 from aircraft, the emissions included in an airport’s net zero claim covers only 1-3% of the total.

Bristol Airport’s aim to become carbon neutral by 2030 coincided with plans to expand. This drew criticism from green campaigners. An increase in flying will almost always result in an increase in emissions irrespective of what happens on the ground.

Bristol Airport is not alone. There are many other examples of airports reducing ground emissions to bolster their chances of being granted permission to expand.

Decarbonising ground vehicles and the airport infrastructure is necessary. But unless the exclusion of flights is indicated when making net zero claims, passengers and the public are likely to remain confused.

When dealing with sustainability claims it is good to have a healthy level of scepticism. As these three examples show, greenwashing can come in many forms. Keeping certain points clear in your mind will help you spot attempts to mislead and misdirect.

Most importantly, the inconvenient truth is that flying is one of the most polluting activities. Cutting back on flying is currently the best way to reduce aviation emissions.

While we will always advocate for industry and Government to do the right thing, the power of public opinion should not be underestimated. As Booking.com’s 2021 consumer survey demonstrates, there can be a ripple effect. With the growth of consumers’ concern over the negative effects of flying, pressure for change can only increase.

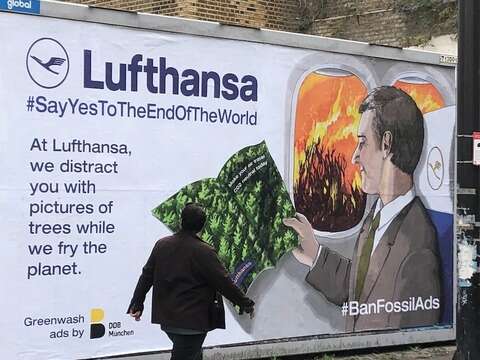

*Cover image courtesy of Brandalism, artwork by Lindsay Grime